I’m late to an appointment—one that can’t be missed. I’ve missed all the others. I miss them because I’ve misplaced language, or maybe this time I’ve lost it, for good ( I’m never certain one way or the other) and I can’t go to the appointment until I find it. In that moment, nothing feels more urgent. I must find language now, and it must be before I leave. I can’t find it later because there is no later. If I leave, intending to continue my search for language when I return, it will be too late.

I must search for it the exact moment I realize it is gone,

or I will never find it again.

I open kitchen drawers and cupboard doors with one boot on. I empty my purse out onto the kitchen table and comb through nickels and cough drops and softened receipts.

The appointment time passes. The sky darkens. My joints ache.

And then it is deep night, no light, and I am on my hands and knees crawling around on the laminate wood floor of my apartment, desperate, angry, ashamed, and searching, and searching, it has to be here, it has to be here somewhere, these are my only words, gifted to me when I was small enough to deserve them, and I cannot afford new ones, I cannot remember how to fashion them myself here at home, I cannot ask for more. Who would I ask? God? What would I say? How do you ask for language without language?

When I have difficulty writing, I often say that I can’t find the words. As if I’m not the one putting them in a particular form. As if, when I find them, they’re already arranged exactly as they should be. And all I have to do is... I'm not actually sure. I don't think I've thought that far ahead. If the words are already out in the open for all to see, where would I come in? What would my role be?

In this dynamic, I become less of a writer, and more of a matchmaker between language and experience. It’s my job to find the appropriate words for appropriate moments, needs, fears, and desires. To select what needs to be selected. General practitioners don’t make prescription medications for their patients themselves: they try to match a medication with a presenting ailment, and then they send their patients to pharmacies. They identify and (hopefully) solve problems, but they don’t create the cure. They aren’t making something out of nothing.

Maybe I used to think of myself like this because

I used to think that language was a cure.

Maybe, as the one who found the language, not the one who created it, I could absolve myself of any wrongdoing if that cure did not work. In a way, I made language an autonomous, sentient thing, that knew how to solve every problem on earth. The words just needed me to drive them from place to place.

But I think that’s where my problem began. The language was active, and I was passive. The language knew, and I did not.

I got used to this dynamic. It was safe. It meant that I didn’t have to think about what happened after the words were released into the world. There would always be experiences, a lot of them terrible, but language would always be there, the right language, for the right experience, and the fit would always be perfect.

I had myself convinced that nothing could be both unspeakable and unwritable. I believed that for a long time. I really did. I relied on it, actually. I survived because of it. I believed it, even though I had experienced certain things that I was unable to put language to. To me, those instances did not prove that, sometimes, language fell short—they reinforced my certainty that everything true had words to describe it, and if it did not have the words, it was not true. If I could not write about an event, then the event did not happen. Nothing existed until I wrote it down.

And that’s where I ended up for many months: The land of nothing. I remembered things I hadn’t ever remembered before—the sort of things the defy the shapes and narratives the human brain likes to sort things into. I encountered situations in the present that left me speechless. Every problem quickly became unsolvable. Every horror unspeakable. Unwritable. There was no language. There was nothing at all.

I want you to know that I’m back, now. From wherever it was that I was or wasn’t. I still have whiplash, and the jet lag is still pretty uncomfortable, and some of my most precious luggage still hasn’t been located, and the things I remembered while I was away are here to stay, but I’m here. I don’t have solutions to the problems I’ve proposed, but I’m here. I’m afraid, but I’m here. I’m afraid, and I’m here.

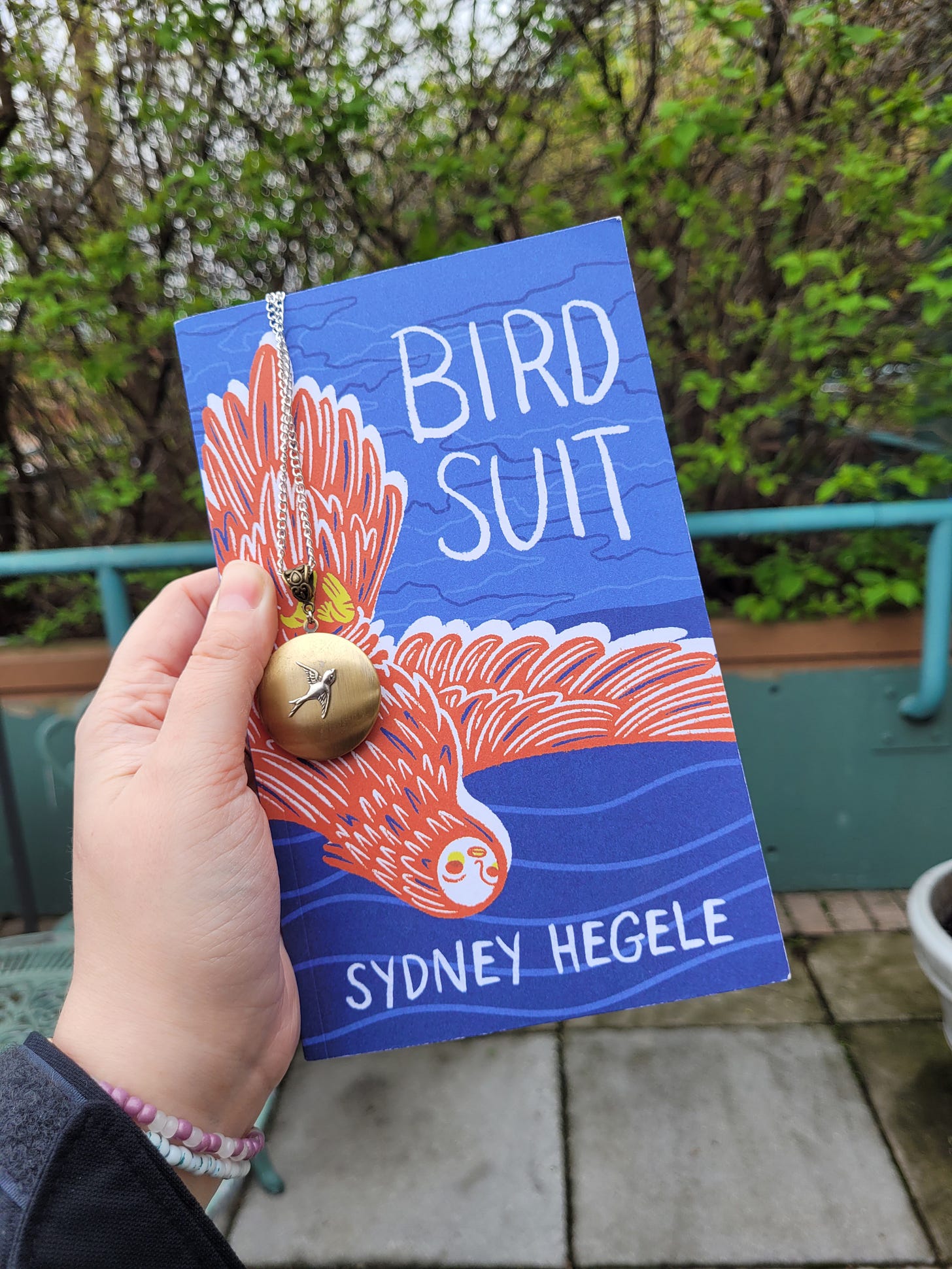

All of which is to say: I’ve been working on a novel called Bird Suit for many years, and it will be yours this Tuesday, May 07, 2024. I have finished writing it—I have finished shaping its meaning—and now it is your turn. I’m a firm believer that both readers and writers create a book together, and that this creation and meaning-making continues on in perpetuity long after the author has finished their portion. When I can’t find the words, this interdependance gives me hope. When I’m afraid, you are here, and seeing you here makes me want to be here, too.

You’re going to hear from me much more than before in the coming week. Some of those words will be to update you on events, press, and reviews. Some of those words will be about Bird Suit in a much more personal way. Some of those words will be more like this.

I do not know if any of them are the “right words”, but they’ll be here with us anyway. We can sort through them together.

With love,

Syd

Bird Suit is out this Tuesday, May 07

A tourist town folk tale of stifled ambition, love, loss, and the bird women who live beneath the lake.

Every summer the peaches ripen in Port Peter, and the tourists arrive to gorge themselves on fruit and sun. They don’t see the bird women, who cavort on the cliffs and live in a meadow beneath the lake. But when summer ends and the visitors go back home, every pregnant Port Peter girl knows what she needs to do: deliver her child to the Birds in a laundry basket on those same lakeside cliffs. But the Birds don’t want Georgia Jackson.

Twenty years on, the peaches are ripening again, the tourists have returned, and Georgia is looking for trouble with any ill-tempered man she can find. When that man turns out to be Arlo Bloom—her mother’s ex and the new priest in town—she finds herself drawn into a complicated matrix of friendship, grief, faith, sex, and love with Arlo, his wife, Felicity, and their son, Isaiah. Vivid, uncanny, and as likely cursed as touched by grace, their story is a brutal, generous tale as sticky and lush as a Port Peter peach.

Praise for Bird Suit

“Mythological creatures and strange relationships shape this beguiling debut novel [which] takes flight thanks to the beauty of its prose.”—Publishers Weekly

“[Hegele’s characters] are broken in every humanly way [yet] written about without sensationalizing them or downplaying them. Bird Suit is a book you will joyfully return to like a complex childhood experience that you desperately want to make sense of and know you can only grow from meditating on.”—Canthius

“Gorgeously strange, marvelously written, bursting with peril, howling with life, Bird Suit is a splendid novel, the kind you don’t want to end, the kind that follows you (listen for the flapping) around.”—Laird Hunt, author of Zorrie and In the House in the Dark of the Woods

“Bird Suit is soft and perfumed as a peach, with a hard, brutal, and wildly strange pit at the centre. This is a special novel, in the sense that it feels like something biological and rare, found in a mossy forest, but it is of our world, however skewed it may seem, because it investigates the difficult, true things of life. Love, sex, friendship, hatred, cruelty, violence, faith. Sydney Hegele’s writing is a delight to read, and their characters are compelling and absorbing. You will love them, cry for them, and shake your fist at them. Bird Suit marks the arrival of an original, brilliant new voice.”—Richard Mirabella, author of Brother & Sister Enter the Forest

Sydney Hegele is a queer Anglo-Catholic writer from the Greenbelt in Southern Ontario. They are the author of Bird Suit (Invisible Publishing, 2024) and The Pump (Invisible Publishing 2021), which was the winner of the 2022 ReLit Literary Award for Short Fiction and a finalist for the 2022 Trillium Book Award. Their essays have appeared in Catapult and Electric Literature, EVENT, and have been featured by Lithub, The Poetry Foundation, and Psychology Today. Their essay collection Bad Kids is forthcoming with Invisible in Fall 2025. Sydney’s work often explores small-town queerness, environmental justice, mental illness, religious life, and the complicated relationships between these things. They live with their husband and French Bulldog on Treaty 13 Land (Toronto, Canada).

I look forward to reading this. Thank you for the effort and sacrifice that went into it.