It's not you— it's me

Diagnostic essays, Tiktok as portraiture, and the dangers of universalism.

Before I wrote personal essays, I thought of essayists like doctors.

A more accurate description would probably be “people who have the authority to diagnose other people’s problems”. To me, the only difference was scale: rather than just making one specific diagnosis, essayists explored their own problems in order to diagnose the collective problems of the world.

Maybe some essayists still do this. Maybe, for some, it isn’t even intentional. But these aren’t the essayists I’m seeking out anymore.

There’s a difference between an essay that uses a personal experience to reflect on or question larger structures, and an essay that equates a personal experience to a universal one.

Think about trying to enlarge a .JPG image on your computer. The first kind of essay resizes the image so that the resolution is clear, rebuilding that small, personal experience into something more meaningful with context and connection. The second kind of essay is that function on your desktop called “fill to fit”, which doesn’t resize the image at all, but rather, attempts to stretch it in its original form until it’s blurry and pixelated.

When I read a personal essay, I want to see the essayist’s truth, and the truth about their world, and the truth about their perception of their world. I don’t want to read a personal anecdote that resolves prescriptively, aka “my personal experience taught me this about everyone’s experience and the meaning of everyone’s life.

I had to unlearn this kind of writing. I’m still unlearning it. Not just because it’s lazy—requiring little introspection—but because it’s not truthful. To call my experiences universal experiences is to put myself at the center of the universe.

I have a hunch that when we try to “reveal” the truth about humanity as a whole, we’re taking our own truth and universalizing it from a place of privilege. When we’re white or straight or cis or able-bodied or living above the poverty line, our stories are the story of humanity—according to popular media, advertising, and the priorities of our social institutions.

When white queer people write about a kind of universal queer experience, for example, we're claiming that those who don't look like us experience queerness in the same way, which they don't. It's clear that any amount of privilege can lead to this dissonance.

To see ourselves represented over and over again throughout our lives gives us the impression that everyone else is exactly like us, and it sends folks on the margins the message that their existence is wrong because they have diverged from the "ideal norm." Here, generalizing isn’t just incorrect: it’s dangerous.

I've noticed a similar thing happening in mental health spaces on TikTok, except there, it isn't always the creator doing the generalizing: sometimes, it's the viewer.

Here's a scenario I see often: a TikTok creator with a dissociative disorder posts a one minute video about a certain aspect of their experience. Viewers see the video out of the context the creator's other videos, and subsequently end up using the one minute of footage to represent that creator in their mind. But out of that context, the video becomes a representation of the dissociative disorder, not of the creator. This leads to either validation of a shared experience with the creator, or a feeling as though the viewer's experience is being excluded from the representation of what the disorder looks like.

The comments below the video then look something like this:

Viewer: I don't experience DID like that. One of us has to be wrong. If it's you, then you're faking.

Creator: I was just talking about my own personal experience. Both of us can experience DID in different ways.

Viewer: If you have DID, then your experience is a representation of the disorder and is everyone's experience.

The problem is that a one-minute long video is just an archive of a single moment in time.

A portrait doesn’t contain the before, the after, or the context of what was happening while it was painted—it can’t contain the full width and depth of a person and their life. Likewise, a short video can’t accurately represent the fullness of a person’s mental illness, and that person’s full experience can’t accurately represent all people who have been diagnosed with said mental illness. Like essays that diagnose the world's problems at-large, videos about mental health are often used to over-generalize and create a false universal experience that is used to reward those privileged enough to match that experience, and gatekeep/discredit those whose experience is different.

I’ve been trying to combat this kind of universalism in my own writing. I say trying because I’m still finding my footing—like a slimly fawn fresh out of the womb, with needle-thin legs and boney knees. Generalizing about the world is pretty easy; seeking the truth in my own life is much more difficult. But it’s necessary work. Dirty, but necessary.

With love,

News from The Marsh

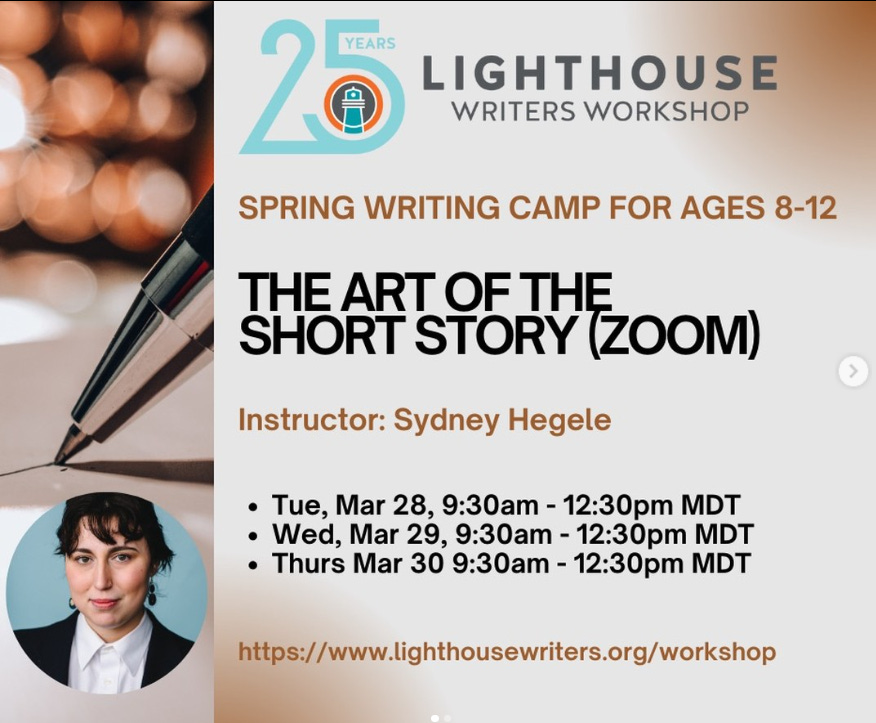

Applications are now open for the Youth Summer Writing Camps through The Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop!

This year I'm teaching my fiction course 'The First Chapter' as part of a week-long Middle School Writing Intensive in Denver, Colorado from July 17-21, 2023.

Applications to all full-day camps can be found here.

*You can use SummerEarlyBird for 10% off until March 1.*

The First Chapter: Fiction with Sydney Hegele

Do you have an idea for a novel but don’t know where to start or how to develop it? In this workshop, we’ll learn the foundations of character, plot structure, and setting through a variety of creative writing exercises(inspiration notebooks, peer interviews, collaborative scene-building, and more!). Later in the week, we’ll dig deep into the mechanics of setting-up a story in the first chapter, and every camper will write the first chapter of their own book. At the end of the week, students will get the chance to do a live reading, sharing part of their first chapter in front of a small audience. Each student taking the fiction specialization in the latter half of the week will receive a personalized list of future reading recommendations based on theirown fiction project. Students are encouraged to use their first chapters to continue writing their books at home after the week’s end.

Also, I’m teaching two March Break Youth workshops over Zoom for the Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop in 2023: Writing Through Climate Anxiety and Introduction to Short Fiction. Registration is here.

I update my events and publishing things frequently on sydneyhegele.com, so take a browse there if you’re ever wondering what I’m up to. And, of course, subscribe to Marsh Mail if you want more of these kinds of musings in your inbox.

Sydney Hegele is the author of The Pump (Invisible Publishing 2021), winner of the 2022 ReLit Literary Award for Short Fiction and a finalist for the 2022 Trillium Book Award. Their essays on life with Dissociative Identity Disorder have appeared in Catapult and Electric Literature, and featured by Lithub, the Poetry Foundation, and Psychology Today. Their novel Bird Suit is forthcoming with Invisible Publishing in Spring 2024, and their essay collection Bad Kids is forthcoming with Invisible in Fall 2025. They live with their husband and French Bulldog on Treaty 13 Land (Toronto, Canada).